For many years, I’ve been following and writing blog posts about one of my heroes, Don Berwick, a physician leader, Obama-era CMS Administrator and one of most eloquent, persistent and effective advocates for quality improvement in health care. In a recent viewpoint article in JAMA, Dr. Berwick and two physician co-authors, Thom Meyer (from Duke) and Arjun Venkatesh (from Yale), argued that the reporting of patient experience of care (satisfaction) metrics should not be “competitive” and should no longer be graded on a curve, which they assert is a cause of “emotional exhaustion” and “burn-out” by physicians. Rather, the co-authors propose that public reporting of patient experience metrics should be based on a “criterion-referenced” rating system in which it is “possible that everyone can get an A” based only on the use of a net promoter score (the answer to the question “how likely would you be to recommend?”) as a “noncomparative assessment.” In a published comment to the article, I offered the opinion that we should not forget the valid purpose that publicly reporting patient experience metrics serves: to inform consumers’ decisions regarding the selection of health care providers. I warned that this purpose would be thwarted if the criteria were selected so that everyone got a “pass” — as is already the case with credentialing and licensing. If we portray all providers as equal in public reporting, then consumers will be forced to base their provider selection decisions on less useful information, such as physician photographs and surnames, university prestige or the amount of marble in the lobby. Let’s not forget the consumer.

Dr. Berwick’s Excellent Perspective

As I previously detailed, at the heart of Dr. Berwick’s lifetime contribution to the field has been teaching us all to distinguish between the “Theory of Bad Apples” and the “Theory of Continuous Improvement.”

Dr. Berwick argues against the Theory of Bad Apples, which is based on the assumption that errors come from “shoddy work” by low-performing doctors, leading to a misguided focus on using metrics to find the bad doctors and embarrass them into doing a better job. According to Berwick, the predictable defensive response by the physicians who are targeted for such remedial attention includes three elements: (1) kill the messenger, (2) distort the data and (3) blame somebody else. When we make the metrics public in an attempt to provide “extrinsic motivation” by creating competition among physicians, Berwick argues that physicians will stop sharing information and working together to improve health care processes. Ultimately, physicians will feel frustrated and disrespected, leading to professional burn-out.

Berwick advocates instead for the Theory of Continuous Improvement.

As shown on the diagram above, the objective of continuous improvement is to shift the entire physician performance curve in the direction of good, while simultaneously reducing variation to un-flatten the performance curve. The basic principles of this theory are:

- Systems Thinking: Think of work as a process or a system with inputs and outputs

- Continual Improvement: Assume that the effort to improve processes is never-ending

- Customer Focus: Focus on the outcomes that matter to customers

- Involve the Workforce: Respect the knowledge that front-line workers have, and assume workers are intrinsically motivated to do good work and serve the customers

- Learn from Data and Variation to understand the causes of good and bad outcomes

- Learn from Action: Conduct small-scale experiments using the “Plan-Do-Study-Act” (PDSA) approach to learn which process changes are improvements

- Key Role of Leaders: Create a culture that drives out fear, seeks truth, respects and inspires people, and continually strives for improvement

The clash of Berwickian thought and consumerism

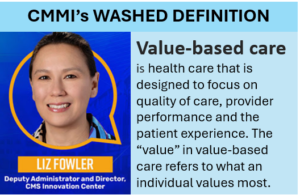

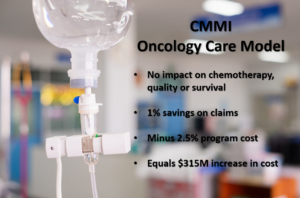

Despite my status of superfan of Dr. Berwick, I have written before about how Dr. Berwick’s views on the centrality of patient freedom of choice clashed with the principles of health economics. In a 2009 paper published in Health Affairs entitled “What ‘Patient-Centered’ Should Mean: Confessions of an Extremist,” he eloquently argued that we should give any patient whatever they wanted, regardless of the cost and regardless of the evidence of effectiveness. I disagreed. Interestingly, in the recent viewpoint article in JAMA, Dr. Berwick and colleagues expressed a perspective that clashes with patients’ freedom of choice. In the earlier paper, Berwick was talking about patients’ choices among alternative health care interventions. In the recent article, Berwick was talking about publicly reported patient experience metrics. Berwick and colleagues pose the question “The Purpose of Measurement?” and then provide a straw-man answer “to create competitive rankings” before explaining what they consider to be the real answer: “to develop mastery in improving patient experience while making health care work less stressful.” That seems to me to be true if the subject was confidential internally reported metrics of patient experience. But the article is making proposals about public reporting of patient experience metrics. The most obvious primary objective of public reporting is to inform the public — prospective patients and consumers — who need information to support their decisions regarding the selection of health care providers. Such decisions, like all decisions, involve selection among available alternatives based on a comparison of the pros and cons of those alternatives. Regardless of whether patient experience metrics are reported on an absolute basis (such as reporting the raw “net promoter scores”) or on a pass-fail basis or on a relative basis (grading on a curve), the consumer making a choice among available alternative providers is comparing the providers to one another. Such is the nature of decision-making.

Do we really want pass-fail?

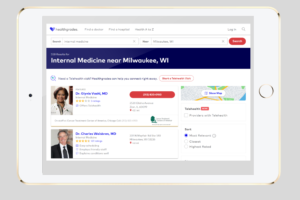

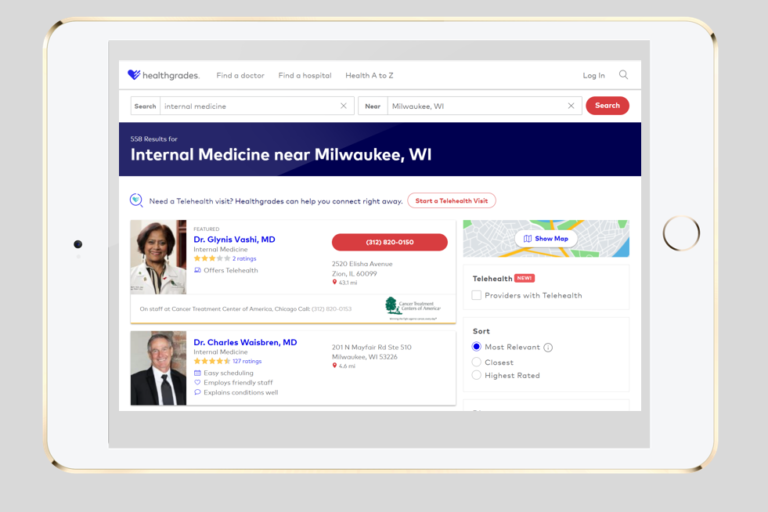

Berwick and colleagues are proposing that public reporting of patient experience metrics be limited to a “criterion-referenced” rating system in which we take the raw measurement data for a provider and compare it to some threshold criteria and then publicly report whether the provider’s performance exceeded the threshold. They explained that they wanted public reporting to be a “noncomparative assessment.” They clarified that in the proposed reporting approach, it should be “possible that everyone can get an A.” We already use that approach for physician licenses, credentials, and privileges. All of these are reported in a noncomparative manner, such that the health care consumer only gets to know whether the provider met the reference criteria. It is a pass-fail system, where virtually all providers pass. That system served a valuable function in the first half of the 20th century to support consumers’ decisions about whether they wanted to seek health care services from a real physician, rather than a snake-oil peddler, a barber, or a quack. That system remains useful in choosing physicians from one specialty rather than another. But now most consumers can choose among many different real physicians in a relevant specialty, a level of choice that is only increasing with the expansion of virtual care and telemedicine. When all the available real physicians in a specialty are publicly portrayed as equal based on licenses, credentials, and privileges, then consumers are forced to make physician selection choices based on other less valuable information. Consumers might choose a doctor based on the prestige of the name of the university at which the provider earned a degree or with whom the provider is currently affiliated. Consumers might choose a doctor based on whether the doctor practices in a physical facility that is impressively tall or that has lots of marble in the lobby. Or consumers might choose a doctor by applying their gender or racial prejudices when viewing the photograph of the provider or considering the last name of the provider in a provider directory web page.

We’ve been debating performance measurement for a long time

Back in the 1990s, I represented the American Medical Group Association (which was then called the American Group Practice Association) on the Committee on Performance Measurement of the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA), which served to oversee the HEDIS measures that were dominant standards at the time. The committee had long and sometimes contentious discussions regarding the future direction of publicly reported performance metrics, trying to find the right balance among competing objectives. To reduce burden, we wanted metrics to be standardized and to avoid the need for chart review or prospective data collection. To increase relevance, we wanted to move toward measures of intermediate outcomes (like blood pressure or HA1C) or patient-reported outcomes, which increased burden and variance. In the two decades since then, measures of experience and satisfaction have become popular across many industries. The trend has favored simplification of customer experience measures, such as by asking “how likely are you to recommend?” and calculating a “promoter score” based on the answer. Promoter scores can be captured with minimal burden and are familiar and easy for consumers to understand and use.

Individual physicians are now subject to a bewildering barrage of performance reports, including report cards prepared by their own physician organizations, health plans, government agencies, business coalitions, and numerous third-party web sites that provide opportunities for patients to rate and offer their opinions about individual physicians. Just like motion picture producers and restaurant owners, physicians face the wrath of numerous critics, some offering insightful feedback, but many offering negativity that may not be fair or even truthful. In the case of motion pictures and restaurants, reports of consumers’ experiences, if valid and truthful, are expected to provide a reasonably complete overview of the outcomes that matter. People go to theaters and restaurants for the primary purpose of having experiences. But, in the case of physician services, the experience is only a secondary outcome. Patients consume physician services for the primary purpose of receiving evidenced based care delivered competently to achieve improved health outcomes. But the consumer of these services may not have the expertise to assess the appropriateness of clinical decision-making or the clinical competence of the care delivery. And patient health outcomes are subject to large variation that may be driven by factors other than the performance of an individual physician.

In this context, the value of publicly reported patient experience measures to inform consumer decisions regarding selection of health care providers is rightfully questioned by physicians.

Five principles for provider performance consumer transparency

First, organizations that publicly report patient experience measures should refrain from publishing quantitative measures unless there is a reasonable sample size and reasonable assurances about the truthfulness of the information being presented. Some publishers of physician report cards assert that any information is better than no information. But that perspective seems driven by the convenience and self-interest of the publishers and should be considered irresponsible and negligent. The ethical obligation of physicians is to consider and use performance metrics that are valid, as detailed in an article in the AMA’s Journal of Ethics.

Second, when raw patient experience metric values are tightly bunched, public comparative reporting of the metrics should not report insignificant differences in a way that misleads the reader into thinking they are meaningful differences. Blindly reporting levels of performance based on percentile ranges has the potential to mislead readers in this way. Therefore, responsible generators and publishers of comparative patient experience performance (or any other provider performance dimensions) should either report raw numbers (to be transparent about the size of differences) or generate performance categories that use natural break points in the performance distribution or that are based on criterion that define performance categories so as to assure that small differences are not exaggerated.

Third, all publicly reported performance metrics should be shown at a level of of aggregation that aligns the metric with the main drivers of systematic variation. Health care delivery is a team sport, so performance metrics that are known to be based primarily on practice-level or organization-level factors should be presented at a practice or organization level. This problem is probably less worrisome in the case of patient experience metrics, particularly when the experience being assessed specifies an individual provider.

Fourth, when publicly-reporting patient experience metrics, the report should be designed to avoid characterizing patient experience as only a performance dimension. It is the nature of patient experience that often times a suitable match between the patient and the provider can facilitate a favorable experience. So, reporting should provide information about appropriately-selected provider characteristics that can inform patients to select the provider that is right for them, while attempting to avoid inappropriate selection based on prejudices. Striking this balance can be devilishly hard.

Finally, organizations that publicly report performance metrics should avoid just reporting patient experience and failing to do the harder work to capture and report meaningful measures of quality and health outcomes. Reporting only experience metrics fails to address the primary objective of the health care consumer to optimize their health status.

Following these principles, we can meet our responsibility to properly inform consumer decisions regarding the selection of health care providers, while reducing the frustration and burn-out of physicians.

5 thoughts on “What should we do when there is a clash between two noble goals: consumer transparency and quality improvement? Five proposed principles.”

(Via email dated Dec 16, 2021. Published with permission.)

Thanks, Rick, for your gracious email and your respectful and well-reasoned essay.

I tend to think that the distinctions among individual clinicians made in rating systems are largely just noise – “common cause variation” – and far less informative than patients might believe that they are. Of course, as always, there will be a small proportion of truly egregious bad performers and, similarly, so heroic positive outliers. But I am not sure that, for most of the distribution, differences in metrics are meaningful or stable.

That said, I am a fan of 100% transparency. Basically, I believe that anything “we” know ought to be open for patients, families, and communities to know. I prefer to get over the fear threshold of sharing the information, and into the difficult and important terrain of how to behave once the information is shared.

My aim is to get us all as far as possible into learning mode, where we can simulate and get motivated by authentic curiosity about how we can do better, all together.

It always impresses me to reflect that the number of times a physician or health care organization has called me long after an encounter or intervention to find out how they really did, or whether their diagnostic hypothesis was correct, or whether the treatment they thought might help did, indeed, help is nearly zero. We are glutted by ratings, but starved for a culture of iterative learning.

Happy Holidays.

Warmly,

–Don

Donald M. Berwick, MD

President Emeritus and Senior Fellow

Institute for Healthcare Improvement

(Via email dated Dec 16, 2021. Published with permission.)

Can’t possibly add to Don’s perfect insights.

Thanks, Rick

Peaceful holidays to you both

Best,

Thom

Thom Mayer, MD, FACEP, FAAP, FACHE

Medical Director, NFL Players Association

Drs. Mayer and Berwick,

Thank you for your thoughtful responses. I particularly appreciate the concept of “authentic curiosity.”

In order to benefit readers of my blog, do I have permission to add your comments to the blog, attributed to you?

Happy and safe holidays!

— Rick Ward

(Via email dated Dec 18, 2021. Published with permission.)

Fine with me, since I didn’t really say anything, but in addition to Don’s “authentic curiosity,” this sentence is a deeply trenchant observation:

“We are glutted by ratings, but starved for a culture of iterative learning. “

That summarizes the essay in a sentence!

Best and happy holidays to you both!

Thom

Thom Mayer, MD, FACEP, FAAP, FACHE

Medical Director, NFL Players Association

(Via email dated Dec 18, 2021. Published with permission.)

On 2nd thought, perhaps this Berwickian observation that data, knowledge, and wisdom are not remotely the same thing but are often confused. We are choking on data, lacking in knowledge, and nearly bereft of true wisdom-which, if present, would guide us to distilling data to knowledge and knowledge to wisdom.

My 2 cents…

Thom

Thom Mayer, MD, FACEP, FAAP, FACHE

Medical Director, NFL Players Association