In a recent health policy viewpoint article in JAMA, Drs. Don Berwick and Rick Gilfillan noted that, although the CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) has done some good during its ten+ years of existence, it has failed to “become the engine that it could be for transforming the nation’s health care finance and delivery.” Drs. Berwick and Gilfillan offer an important perspective, because they were both part of the birth and early formative phase of the CMMI. Dr. Berwick was the administrator of the CMS during 2010-11, when CMMI was established, and Dr. Gilfillan served as CMMI Director from 2010-13. Both are people I admire greatly and consider to be fellow travelers on the road to a better health care system. Dr. Berwick is among my health care heroes (as described in depth in a blog post I wrote almost 10 years ago), and I had the opportunity to work closely with Dr. Gilfillan in more recent years when he served as CEO of Trinity Health and Reward Health helped Trinity to establish the IT and analytics infrastructure to support their efforts to launch ACOs across the country.

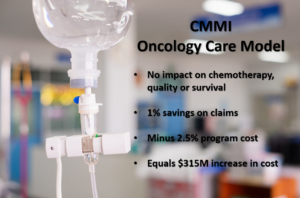

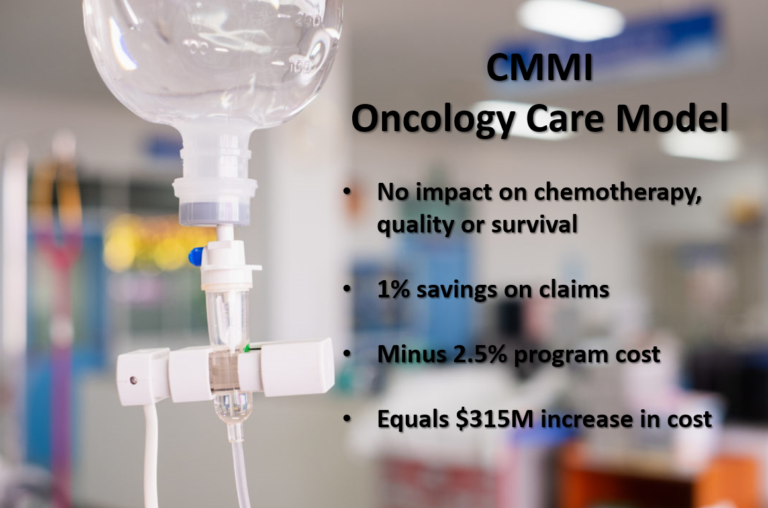

In the JAMA viewpoint paper, they noted the generous $20 billion funding allocated to CMMI for 2011 through 2029, and described the results of tests of 55 payment and care models that have been conducted so far. They acknowledged a recent independent review by Brad Smith in NEJM concluding that only 5 of the models resulted in significant financial savings. They noted that only 4 of the models have been certified by the CMS actuary for “national scaling,” and that only 2 of the models have actually been “scaled” — one involving lifestyle change supports to reduce diabetes risk, and the other pertaining to the value of downside risk incentives for advanced ACOs.

Berwick and Gilfillan’s Six Recommendations

Drs. Berwick and Gilfillan, oriented as always toward continual improvement, offered six recommendations for the “reinvention” of CMMI, which I have paraphrased below.

| Recommendation 1: Connect CMMI agenda to a “shared vision” embraced by the rest of the Department for Health and Human Services. |

| Recommendation 2: Make ACO model mandatory for all Medicare participating clinicians and hospitals — and transition to total cost of care capitation “as much as feasible” |

| Recommendation 3: Focus more on health equity |

| Recommendation 4: Focus more on testing delivery system redesigns, rather than just payment models. |

| Recommendation 5: Focus more on collaboration with private-sector providers, payers and academics. |

| Recommendation 6: More agility and risk-taking, less “clearance” bureaucracy. |

My Take: Yes, but they don’t really solve the critical mass problem

I agree with all six of the recommendations offered by Drs. Berwick and Gilfillan. However, they fail to emphasize what I consider to be the root cause for the disappointing transformational impact of CMMI: the failure to achieve critical mass.

The CMMI has focused on testing payment models, rather than delivery system redesign models, because they recognized that Medicare is just one of many payers. Medicaid is largely shaped by states. Although HHS provides some services through Federally-Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and the Indian Health Service, and the US Department of Veteran’s Affairs (VA) provides some services to veterans, the vast majority of actual care delivery in the US is by private health care provider organizations — organizations that are also financed by many other payers. So, although the incentives provided through Medicare payment models can certainly be influential on the decisions of provider organization leaders and individual providers, those incentives are diluted by potentially conflicting incentives from other payers.

In the context of CMMI payment model tests, this dilution is made worse by the fact that the incentives do not even apply to all care of Medicare patients, since the payment model may focus on only a subset of Medicare patients (such as in episode-based models) and the patients may receive services from other providers not subject to the incentives. Finally, the incentives for many of the CMMI-tested payment models have been weak even before being diluted by other payers. Back when Drs. Berwick and Gilfillan were at CMS, they advocated for incentives that were stronger, including both upside and downside risk. However, they faced strong pushback from provider organizations and they backed down. The first generation of the “shared savings” programs allowed the vast majority of providers to either opt out entirely or sign up for “upside-only” incentives. I worked with more than a dozen provider organizations in that era to establish ACOs and CINs, and can report that, although such entities did some good to bring doctors and hospitals together to pursue quality improvement, our experience was that the weak, diluted incentives failed to achieve a critical mass necessary to motivate organizations and individual providers to make uncomfortable and disruptive changes in clinical practices and to make costly investments in the technology and human resources needed to support changes worthy of the word “transformation” or even “redesign.” When Drs. Berwick and Gilfillan wrote their “recommendation 2” — the first four sentences were about making ACOs mandatory, and then they slipped an elephant into the last sentence: “Part of the expansion [of ACOs] should include, as much as feasible, progressing to capitation of ACOs for total cost of care.” This bold proposal is phrased with an understandable timidity, given their past experiences and their admirable pragmatism.

What is the threshold for Critical Mass?

I feel confident, based on years of relevant experience, that CMMI is nowhere near achieving critical mass — even if they were to accept the recommendations of Drs. Berwick and Gilfillan. My experience suggests that, even if the entirety of Medicare were to be total-cost-of-care-capitated through ACOs, that might still not achieve critical mass to motivate real transformation of the health care delivery system.

When I started my career at Henry Ford Health System in the 1990s, half of our patients were members of our own HMO, the Health Alliance Plan, making them essentially capitated. The other half were reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis. Our experience taught us that fee-for-service is the dominant gene, as even 50% capitation was sufficient only to motivate incremental improvements, not transformation. Our experience has taught that when a medical group, with employed doctors and no ownership of hospitals, decides to focus exclusively on serving Medicare Advantage patients (effectively capitated), they are able to justify more substantial investments in technology and human resources for population health management and more transformational care model redesign. So, I’m unclear about what is the threshold level of risk that motivates care model transformation, but my somewhat-informed opinion is that the threshold is probably about 75-80% capitation (or the equivalent mix of risk-sharing). Furthermore, such an incentive structure has to be stable for a sufficient number of years for the idea to sink into people’s heads or for people with impenetrable heads to retire or move on.

In making this 75-80% capitation-equivalent guess, I do not want to leave the impression that the threshold is simple or clear. There are different types of critical mass that must be achieved. There is a critical threshold of “mind-share” of individual clinicians — a function of the proportion of the patients they see on a day to day basis and a proportion of their individual compensation subject to the incentives. There are critical mass thresholds in clinic-level health care delivery processes — such as a minimum number of patients for whom care management services are justified to keep a care manager busy doing important work rather than just providing concierge services or serving as an extra pair of hands in a busy clinic. There are critical mass thresholds for infrastructure such as information technology and physical facilities. There are critical mass thresholds that apply to brand recognition and negotiating power in a local, regional or national market. And, there are critical mass thresholds that apply to the size of a population in relation to the variance of important metrics so as to provide a minimum level of actuarial stability and to support meaningful performance comparisons.

Also, I don’t want to give the impression that health care provider organizations or individual providers are just passive parties responding to extrinsic motivations. Leadership matters. Culture, vision and values matter. My experience with many different organizations has taught that when trustworthy leaders articulate a compelling shared vision that reflects the values of the organization and the community, the members of the organization can be inspired to achieve great things together even with weak extrinsic incentives.

My Two Additional Recommendations for CMMI Reinvention

Following the lead of Drs. Berwick and Gilfillan to seek continual improvement, I offer the following two additional recommendations to the Biden administration regarding the reinvention of CMMI:

| Recommendation 7: CMMI should invest in understanding the critical mass thresholds required for success of proposed payment models and care delivery models, including conducting or funding research to develop the knowledge base regarding incentives, and conducting simulation modeling of the proposed models in the larger organization and community context to establish the plausibility that proposed models can achieve critical mass. |

| Recommendation 8: CMMI should refrain from pursuing tests of payment models and care delivery models if the plausibility of achieving critical mass has not been established, and should refrain from drawing conclusions regarding the effectiveness of models unless critical mass has been achieved. |

3 thoughts on “Berwick and Gilfillan offer six recommendations for reinventing CMMI. My response is yes, but they don’t address the #1 issue: failure to achieve critical mass.”

Hello Dr. Ward.

Thanks for sharing your insights. As I look back on my experience working in both the US and Canada Over the past 25 years and leading major system changes through restructuring or technology implementation ( often called transformation but really mostly incremental in outcomes) I think your right about limits of incentive models. I’ve seen significant improvements occur in billion dollar health ecosystem services with small financial incentives when driven by passionate executives , but even then the impact on population health was negligible. Yet, at scale, even with a nationalized insurer model in canada we seem unable to muster the political will to affect major change in clinical practice patterns at a population level to a large part, in many health system leaders opinions, due to the separate private provider model for most physicians- in short the rate limiting factor is the structural relationship between the physicians the health system itself as much as how everyone is paid. – my 2 cents -(CND but still more than a penny for my thoughts!). Kind regards. Yoel

Yoel, it is excellent to hear from you! Thanks for commenting. In Ontario, the impact of “Ontario Health Teams” has been similarly uninspiring, which is not surprising since it resembles an adaptation of the ACO/CIN model in the US, but lacking any meaningful economic incentives for physicians to make changes and funding to support practice-level infrastructure investments. The result is a lot of meetings providing some beneficial opportunities for communications across hospital/professional boundaries, but no “critical mass.” I agree with your observation that the structural relationship between physicians and the health system is also an important barrier to transformation in the True North.

Pingback: What is missing from the CMS Innovation Center five year vision? – Reward Health