During the last 20 years, we have experienced wave after wave of new frameworks for improving health care. Each had its own terminology, ardently promoted and enforced by its zealous advocates. Each had a lifecycle that began with a long incubation period, followed by a period of explosive growth in popularity and influence, rapidly leading to unrealistic expectations, followed by a period of decline during which the framework was declared to have been ineffective. We’ve been through health maintenance, outcomes management, clinical effectiveness, managed care, disease management, chronic care, care management, practice guidelines, care maps, evidence-based medicine, quality functional deployment, continuous quality improvement, re-engineering, total quality management, and six sigma. We’re still in the thick of lean, patient-centered care, value-based benefits, pay-for-performance and accountable care.

Four things I’ve noticed about this lifecycle of health care improvement frameworks:

- They are formulated by conceptual thinkers, but then get taken-over by more tactically-oriented people. The tactical folks often focus too much on the tools, terminology and associated rituals. The framework always gets “simplified” to be more suitable for mass consumption. For example, continuous quality improvement somehow morphed into being primarily about assigning a timekeeper during team meetings and communicating progress on a felt-backed “story board,” rather than finding people with systems-thinking talent and applying that talent to understand sources of variation in complex processes.

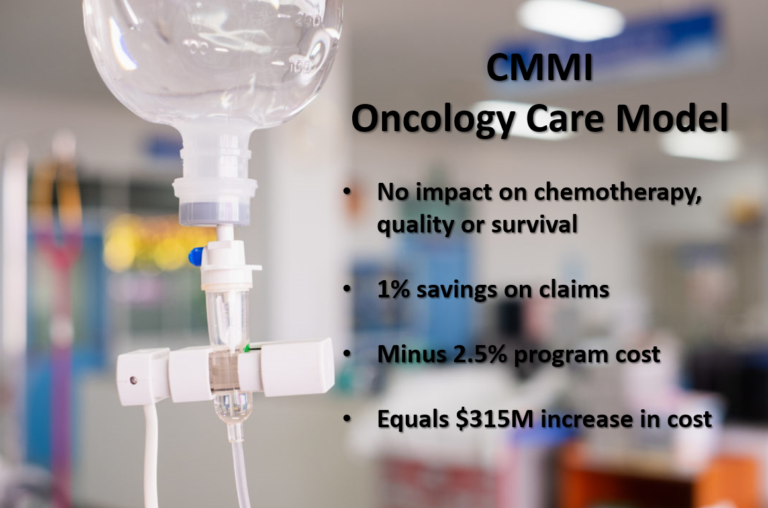

- During the early part of the growth phase, the advocates are always desperate for examples of success, and shower a great deal of attention on early projects that are described using the terminology of the framework and that appear to have succeeded. The desperation usually leads advocates to lower their standards of evidence during this phase. This leads to over-promising and unrealistic expectations. It stimulates lots of superficial imitation by people interested in hopping on the bandwagon. And, it plants the seeds for the eventual decline, when people determine that their inflated expectations were not met.

- The decline phase, when the framework is declared to be ineffective, seems to always happen before the framework was ever really implemented in the way envisioned by the original formulators during the incubation phase.

- All the frameworks are really just restatements of the same underlying concepts, but with different terminology and tools, and different emphasis. In other words, they all have the same anatomy, but different parts of the anatomy are emphasized.

This last point reminds me of the “humunculus,” also called the “little man.” When I was in medical school in the late 1980s, we used heavy text books that generally did a bad job of teaching the information. One notable exception was clinical neuroanatomy. We used a small, paperback text book playfully entitled “Clinical Neuroanatomy Made Ridiculously Simple” by Stephen Goldberg, MD. It contained a collection of clever drawings designed to explain the structures and functions of the brain and spinal cord. Perhaps the most famous of the drawings was the humunculus.

This drawing was adapted from earlier work by an innovative neurosurgeon named Wilder Penfield, who invented new surgical procedures for patients with epilepsy during the late 1930s. During those procedures, he used electrodes to stimulate different points on the surface of the brain. He drew diagrams similar to the drawing above showing that the surface of the brain contained a little man hanging upside down. The diagram shows that a disproportionate portion of the brain surface is dedicated to the sense of touch and muscle movements in certain parts of the body. Lots of brain surface is dedicated to highly sensitive and nimble areas like the lips, tongue, hands and feet. Very little brain surface is dedicated to the arms, legs and back. Many anatomic illustrators have drawn the humunculus as a cartoon character showing how this disproportional emphasis on different parts of the body looks on the little man.

The humunculus is a great teaching tool, making it easy to remember these aspects of clinical neuroanatomy. But, I think the humunculus is also a useful metaphor for the distorted emphasis that various health care improvement frameworks have placed on various parts of the underlying anatomy of health care improvement.

Framework |

Emphasis |

| Health maintenance | Preventive services |

| Outcomes Management | Measurement of function, patient experience and health status |

| Clinical Effectiveness | Measurement of outcomes in real world settings, rather than laboratory controlled conditions |

| Managed Care | Prospective review of appropriateness of referrals, procedures and expensive drugs, and retrospective review of cost of care |

| Disease Management | Role of nurses in training patients to be more effective in self-management |

| Chronic Care | Teamwork in primary care clinic and importance of organizational and community environment |

| Care Management | Role of nurses in coordinating services delivered by different providers and in different settings |

| Practice Guidelines | Consensus about which ambulatory services are appropriate in which situations |

| Care Maps | Consensus about the sequence of inpatient services for different diagnoses |

| Evidence-based Medicine | Weight of scientific evidence about efficacy of a service (without regard to cost) |

| Quality Functional Deployment | Focus on the demands made by patients |

| Continuous quality improvement | Small experiments to determine if incremental process changes are improvements |

| Re-engineering | Designing new processes from scratch, rather than making incremental changes |

| Total Quality Management | Importance of organizational culture and management processes |

| Six Sigma | Focus on reducing frequency of defects |

| Lean | Focus on eliminating non-value-adding process steps and reducing cycle time |

| Patient-centered care | Focus on the needs of patients and the involvement of patients in their own care |

| Value-based Benefits | Financial incentives to motivate patients to comply with recommended treatments that reduce overall cost |

| Pay-for-performance | Financial incentives to motivate individual physicians to improve quality and reduce cost |

| Accountable care | Financial incentives to motivate health care organizations to improve quality and reduce cost |

Over the years, I have assimilated the concepts, terminology and tools from these various improvement frameworks into an approach that attempts to achieve balance, with each aspect of the framework shown without over-emphasis.

This framework puts the patient in the center, surrounded by the health care processes, which are surrounded by improvement processes. It attempts to balance between focusing on care planning (the clinical decision-making regarding what services are needed) vs. focusing on care-delivery (the teamwork to execute the care plan and provide health care services to the patient). It balances between measuring outcomes and measuring quality and cost performance. It balances between implementing best practices through guidelines and protocols vs. improving practices through performance feedback and incentives. By avoiding a distorted over-emphasis on any one part of the anatomy, hopefully it can have greater lasting power than some of the more humunculus-like frameworks that have come and gone. This framework is described more fully here.