As shown in the following graphic recently published by the Healthcare Intelligence Network, it has become common practice to use “case load” as a metric for the productivity of nurses in case management programs or as a measure of the intensity of a case management intervention. More broadly, case load has been used for these purposes across many wellness and care management interventions, including chronic disease management, high risk care coordination, wellness coaching, care transition coordination, and other types of programs involving nurses, physician assistants, nutritionists, social workers, and physicians.

If everyone is doing it, it must be right. Right?

In my opinion, case load is almost always the wrong measure to use to assess productivity or intervention intensity.

The graphic above indicates that 38% of case management programs have a case load between 50 and 99. Let’s say that one of those case management programs told you that they had a case load of 52. That literally means that the average nurse in that case management program has a list of 52 patients (on average) that are somewhere between their enrollment date and their discharge date for a the program. That could mean 52 new patients every day for an intervention consisting of a single 5 minute telephone call. Or, it could mean 1 new patient each week for a year-long intervention involving an extensive up-front assessment and twice-monthly hour-long coaching calls. Or, it could mean 1 new patient each week for a year-long intervention consisting of a 20 minute enrollment call and a 20 minute check-up call one year later. In that context, if I tell you that my case management program has an average case load of 52, how much do you really know?

Some case management programs try to fix this problem by creating an “acuity-adjusted” or “case-mix-adjusted” measure of case load. In such a scheme, easier cases are counted as a fraction of a case, and more demanding cases are counted as more than one case. Such an approach requires some type of a point system to rate the difficulty of the case. Some case management vendors charge a fee for each “case day,” with higher fees associated with “complex” cases, and lower fees for “non-complex” cases. You can imagine how the financial incentives associated with the case definition can affect the assessment, and how reluctant the case management vendor would be to discharge cases, cutting off the most profitable days in the tail-end of a case when the work is light.

But these “adjustments” are missing the fundamental point that case load is a “stock” measure, while the thing you are trying to measure is really a “flow.” A stock is something that you count at a point in time, like the balance of your checking account or the number of gallons of gas left in your tank. A flow is something that you count over a period of time, like your monthly expenses or the number of gallons per hour flowing through a hose to fill up your swimming pool. The work output delivered by a case management nurse is something that can only be understood over a period of time.

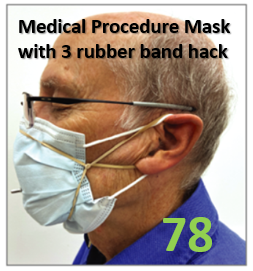

In my experience, the best approach to measuring case management productivity and intensity is to follow “cohorts” of patients who became engaged in the intervention during a particular period of time to track how many minutes of work are done for each period of time relative to the engagement month, as shown below.

This graph shows that, during the calendar month in which a patient became engaged, an average of 50 minutes of nursing effort was required. For individual patients, the nursing effort could, of course, be higher or lower. Some patients require more time to assess. Some patients may have become engaged at the end of the calendar month. Some patient may drop out of the program after the first encounter. But, on the basis of a cohort of engaged patients, the average was 50 minutes. In subsequent months, the average minutes of nursing effort typically decreases, after initial enrollment, assessment and care planning effort dies down. Over time, depending on the intended design of the intervention, the effort falls off as most patients have either been discharged by the nurse, have chosen to drop out, or have been lost to follow up. This graph is a description of the intensity of the case management intervention. In this example graph, the cumulative nursing time over the first 16 months relative to the month of engagement is 234 minutes, which could serve as a summary measure of intervention intensity. If nursing minutes data are not available, some “work-driver” statistics could be substituted, such as the number of face-to-face or telephonic encounters of various types. These could be converted to minutes based on measured or estimated average minutes of effort for each of the statistical units.

This type of graph can be created for different engagement months and compared over time to determine if the intervention intensity is changing over time. It can be created for one nurse and compared to all other nurses to determine if the intervention process delivered by that nurse appears to be similar or different than other nurses.

Then, to assess productivity, the total number of nursing minutes can be measured, and compared to the expected number of minutes for cases of the same type and the same mix of “month numbers” in the case intensity timeline.

The implications of this for Accountable Care Organizations is that information systems to support wellness and care management should be designed to explicitly capture the engagement date and the intended type of wellness or care management intervention in which the patient is becoming engaged. Such systems should also capture the discharge dates, statistics about the quantity and types of wellness or care management services delivered to engaged patients, and preferably the number of minutes of effort required for each of those services.

Some people may object to this approach because it implies that the patient is being subjected to a “cook-book” intervention that fails to take into account the uniqueness of each patient. And, they argue that they cannot specify up front the type of wellness or care management program in which the patient is becoming engaged, because they have not yet completed an assessment. But, I would argue that nothing in this approach assumes that each patient is treated the same. This approach merely looks at a population of patients receiving a particular intended type of intervention program. Although each patient may follow a different path and receive a different mix and quantity of case management services, the overall mix and timing of services for a population of patients can be assessed. If this mix and timing is not generally constant over time, then you are dealing with a process that is not in control, a problem that must be solved before meaningful program evaluation of any type can be done.

4 thoughts on “Why “case load” is not a good metric for case management productivity or intensity”

Hello there,

My name is Lena Trolz LMSW and currently work as a case manager in our local hospital which has 442 beds. Our “Patient Care Management” Dept consists of about 30 patient care managers, with about 20 to 22 working during the week days. As many hospitals are now tasked with budget changes due to the Covid pandemic; our dept is now tasked with giving measurable data to provide our productivity/worth. Currently we are measured by the number or notes charted on patients seen during the work day. This done through a tool within our charting system. It indicates how many notes have been charted in an 8 hour day by each person in our dept. I feel this measure does a disservice to what the case manager actually does and deals within a days work. I really appreciate this article and wondered if you could possibly suggest any further data/resources that I could review to bring a thoughtful argument on other measures/metrics to provider to the financial leadership.

Ms. Trolz, thank you for your comment. It is great to hear about someone getting value from a blog post that is 11 years old! I have recently done more work on the topic of measuring productivity, doing clinical capacity planning, and managing wait lists. So, I’ll do an updated blog post on this topic soon, urged by your helpful nudge.

I too would be interested in hearing more. I work in an outpatient care management setting with significant variances in caseloads among 15 care managers, ranging from some care managers carrying 9 patients and some carrying 50. They are each serving different cohorts of patients that require different interventions over different spans of time, as you mentioned. Management is trying to accurately measure productivity as a department, especially with much of our staff working from home and they do not like these numbers. In addition to volume, we also have a way of tracking what we call ‘communication events’ per patient, as a ‘count’ and in ‘minutes’. these include calls, in person meetings, email or any communication done with other members of the healthcare team regarding the patient. we have looked at this , however it is very tedious and difficult to define a ‘goal’ on what exactly is productive. Would it be a good idea to first start with one ‘cohort’, define the total number of minutes expected for this cohort and then a comparison of actual minutes to see how far off we are? there are also many variables to account for, including differences in care management among care managers, documentation, etc. Thank you for your time and your post!

Jayme, thank you for taking the time to post a comment. I’m glad to hear that you have access to communication event statistics. I agree with your idea of starting with one cohort. As you imply, it can be challenging to clarify goals and what constitutes productivity. I suggest starting with the portion of your care management work that most resembles a “protocol” — where you can most clearly define the type of problem being addressed and a generally-expected set of service activities (AKA “interventions”, “communication events”, “encounters”, “contacts”, “touch points”) that can be designed to address the problems and/or accomplish goals relevant to the problem. Conversations with your colleagues to clarify the top few case types and the associated ideal care process will be valuable even before you start doing any metrics. For the metrics to be accepted by both care managers and management as valid and to be received and used with curiosity rather than defensiveness, getting consensus up front is essential. To make it easy on yourself at first, keep it simple and define things to take advantage of the data elements you already have been collecting. I’m eager to hear how it goes, and happy to offer advice along the way (see my contact info).