Note that the following write-up is now almost 20 years old! (How did that happen?) Amazingly, the debate about the role and frequency of mammography in the 40-49 age group has raged on the entire time since then. This case study demonstrates the real-world use of the “explicit method” proposed by one of my “health care heroes”, David Eddy. Eddy’s approach involves using decision-analytic models and cost-effectiveness analysis to interpret evidence and incorporate our values to inform practice guideline development. This case shows that the explicit method is not just a “purist” methodology. It is a practical method of achieving agreement among physicians that started the process in angry disagreement.

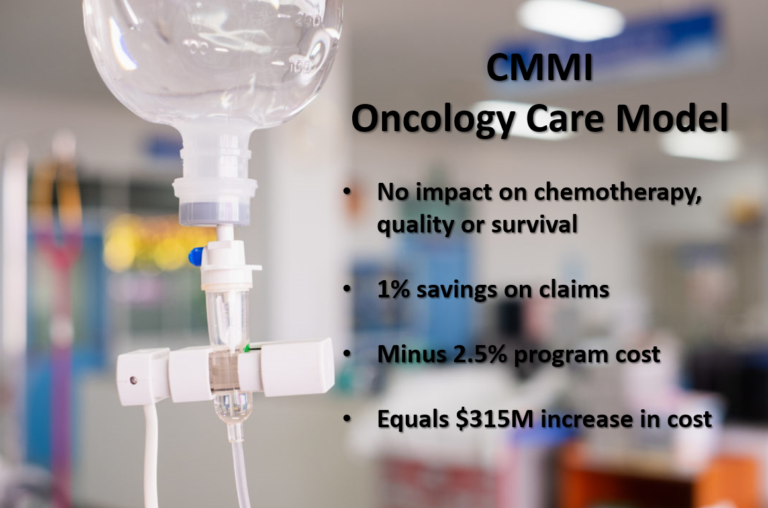

In the last two decades, our field has largely retreated from difficult discussions about cost-effectiveness and the rational allocation of limited resources — the dreaded “R” word. In the recent debates about health care reform, those opposing reform talked of “death panels” and berated the U.K.’s NICE program which espouses some of the same principles as we used in this case. Such harsh talk has replaced the thoughtful, principled discussions we were having at the Henry Ford Health System and in the field in general back then. True health care reform will require that we go back and cross at this light.

— R. Ward, MD Jan 27, 2010

Background

As shown in the newspaper clipping below, the role of mammography in the 40-49 age group has long been controvertial.

Many organizations recommend mammography during the 40’s, including the American Cancer Society, the American College of Radiology, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Medical Women’s Association, the National Alliance of Breast Cancer Organizations, and the National Breast Cancer Coalition. Other organizations argue that the benefits of mammography have not been proven, and therefore mammography should not be offered until age 50. These organizations include the American College of Physicians, the American College of Family Practice, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the National Women’s Health Network, the National Center for Medical Consumers, the Darmouth Center for the Evaluative Clinical Sciences, the Canadian National Task Force on the Periodic Examination, and the United Kingdom Public Health Policy Board.

Within Henry Ford Medical Group, this same debate was also raging. In May, 1991, the HFMG Operations Committee approved a Consensus Guideline calling for bi-annual screening in 40-49 age group. Then, in October, 1993, the HFMG Consensus Guideline was updated based on recently published results of the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. The new consensus group formulated a recommendation which said “women age 40-49 not in a high risk group should carefully consider the risks and benefits before scheduling a mammogram.” This draft was approved by the Clinical Practice Committee, but was subsequently rejected by the Operations Committee. Strong letters of opposition were sent to HFMG leadership from the Department of Surgery and the Division of Breast Imaging. This led to a decision by Clinical Practice Committee to re-do analysis using explicit methods.

Objective

A multi-disciplinary team was commissioned by the HFMG Clinical Practice Committee to use an explicit methodology to conduct a clinical policy analysis and develop specific clinical policy recommendations regarding the role of screening mammography for average risk women age 40-49.

Methods

A multi-disciplinary team was assembled to conduct the analysis and formulate policy recommendations. This team included the Chairmen of the departments of Radiology, Obstetrics & Gynecology, and Surgery. It also included the Division Head of Breast Imaging, two general surgeons from the breast clinic, a staff oncologist, a Division Head in Internal Medicine, the Clinical Director of Family Practice, the Section Head of Epidemiology, the Associate Medical Director of the Health Alliance Plan (HMO). The team was led by the Director of the Center for Clinical Effectiveness.

Based on information from the medical literature, internal HFMG data, and expert opinion of team members, a mathematical model was developed and refined in order to gain a greater understanding of the implications and shortcomings of existing scientific evidence and to estimate the health and economic outcomes (with ranges of uncertainty) for three alternative plans: (1) do not recommend mammography until age 50, (2) recommend a program of bi-annual mammography during the 40-49 period, and (3) recommend a program of annual mammography.

Results

Results of Mammography Policy Analysis

As shown in the figure above, compared to not recommending mammograms, a program of 5 bi-annual mammograms for the 2,500 HFMG women entering their 40’s would add about $1.5 million to the net health care cost for the group (90% range of certainty: $918k – $2.1 million). This program could be expected to save between one and six lives, resulting in a gain of about 141 life years (43 – 244). This represents an expenditure of $440 thousand per life saved (undiscounted). With discounting of health and economic outcomes, this represents an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $34 thousand per life-year gained (15k – 120k). Earlier detection, in addition to saving lives, would permit the use of breast conserving procedures in about 2 more women, and would permit non-systemic treatment for 4 more women. In addition, such a program of bi-annual mammography could lead to added piece of mind for about 1,700 women receiving all negative screening results. On the down side, 59 more women would suffer the fear, inconvenience and risk associated with falsely positive mammogram leading to a negative biopsy, and an additional 650-950 women would suffer the unneeded worry associated with false positive mammogram results.

The full model results, presented in a table called a “balance sheet”, also shows the calculated health and economic outcomes associated with Plan C, offering annual mammography during the 40-49 age range.

Compared to bi-annual mammography, a program of 10 annual mammograms during the 40’s would cost an additional $900 thousand, saving an additional 0-1 lives for an estimated gain of 26 more life-years (1 – 58). This represents an expenditure of $1.4 million per life saved (undiscounted). With discounting, this represents an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $108 thousand per life-year gained (42k – 1.8 million).

Conclusions

On the basis if these estimates, the team recommended bi-annual screening mammograms in average risk women age 40-49. This guideline was intended to serve as a “best-practice”, “minimum practice”, and “maximum practice” guideline, as summarized in the following statement which was unanimously endorsed by the team: “Unless documented, patient-specific circumstances dictate otherwise, it is important to offer screening mammograms every two years during the 40-49 age period. More frequent mammograms are not routinely needed for average risk women during this age period.” This guideline statement was incorporated into the existing HFMG clinical preventive services guideline for breast cancer screening.

Postlude

Shortly after this guideline was approved, a meta-analysis of mammography trials was published in JAMA. The abstract stated “The results of our meta-analysis suggest that screening mammography reduced breast cancer mortality by 26% (95% CI 17-34%) in women aged 50-74 years, but does not significantly reduce breast cancer mortality in women aged 40-49 years.” (emphasis added). The body of the manuscript stated “there were only three clinical trials in which women aged 40-49 years underwent two-view mammography and had 10-12 years of follow-up; in those, the relative risk for reduction in breast cancer mortality . . . was 0.73 (95% CI, 0.54 to 1.0) after 10-12 years of follow-up.” Although the abstract suggested the opposite conclusion as the HFMG clinical policy analysis, apparently based on a confidence interval that touched zero, the point estimate of mammography effectiveness in the 40-49 age group was actually more favorable than the HFMG analysis (27% vs. 25% risk reduction). The fact that the assumptions and calculated outcomes were explicitly documented in the HFMG made this potentially consensus-breaking piece of new information and put it in its appropriate context. This example also illustrates the decision-making criterion implied by the clinical trial and meta-analysis literature: if an intervention has a positive effect which is 95% or more likely to be greater than zero, then it is implicitly recommended, regardless of the magnitude of the outcome in relation or the cost. The explicit method permits policy-makers in health care organizations to use a more sophisticated and philosophically defensible criteria based on an assessment of benefits, costs, and the uncertainties associated with each.

4 thoughts on “Using Eddy’s Explicit Method to Develop Practice Guidelines for Mammography in the 40-49 Age Group”

Pingback: Reports of the death of Cost-Effectiveness Analysis in the U.S. may have been exaggerated: The ongoing case of Mammography

Pingback: To resolve conflicts, re-frame polar positions as optimization between undesirable extremes. But, sometimes there is no way to win.

Pingback: Defensible COVID-19 vaccine prioritization policy will require bravery and explicit principles and analytics. We offer example principles and propose a 6-step process. – Reward Health

ANOTHER UPDATE – 34 YEARS LATER!

Crazy how time flies, but the underlying issues remain frustratingly constant.

Today (April 30, 2024), the US Preventive Services Task Force published in JAMA an updated version of their breast cancer screening guidelines (https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2818283 ). They concluded the same thing we concluded 34 years ago:

“The USPSTF recommends biennial screening mammography for women aged 40 to 74 years. (B recommendation) The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening mammography in women 75 years or older. (I statement) The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of supplemental screening for breast cancer using breast ultrasonography or MRI in women identified to have dense breasts on an otherwise negative screening mammogram. (I statement)”